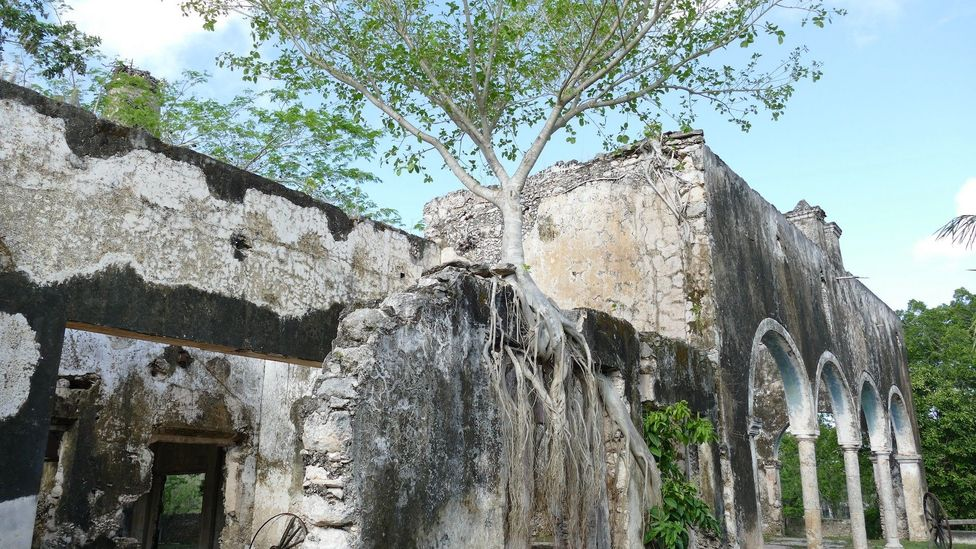

I caught a glimpse of a crumbling stone wall that was being slowly engulfed by crawling vines and alamo trees as I made my way through dense jungle flora. What may have been been a magnificent courtyard was surrounded by the wall. It was a portion of a bigger hacienda, one of the numerous magnificent estates that Yucatan’s 19th-century henequen-rope industry had funded and which are now all but shadows of their former glory.

On a motorcycle trip through the Yucatan Peninsula, I stumbled upon these ruins. A local guide took me off the major roads and into the lush forest to show me another layer of Yucatan’s history and heritage: the abandoned henequen haciendas. I’d expected the emphasis of my bike expedition to be the area’s more well-known claims to fame, its cenotes, and ancient Maya sites.

There are hundreds of these haciendas on the peninsula, many of which cover thousands of acres, despite the fact that few tourists are aware of them. They once stood for the richness and power of the peninsula, but after a rapid decline in fortune, they were abandoned in the 1950s. While some of the remains may be seen from the side of the road, some require a local knowledgeable guide with good eyes, and some have been left for nature to take its course, a few have been reclaimed for a second life.

I planned a 165km loop of backcountry roads just south of Merida over the course of two days and rode my motorcycle there. I visited four separate haciendas, each of which had a distinctive history and was in a state ranging from dilapidated decay to wonderfully restored.

The highway gave way to tranquil towns where the streets were still unpaved and the forest had woven itself into the roads as I passed the village of Homun, about 60 kilometers southeast of Merida. I was struggling with the terrible heat and humidity as I made my way toward Kampepén, the first historic hacienda on my makeshift trail.

Yucatan – The Forest of Dilapidated Mansion

Yucatan saw extraordinary wealth throughout the 19th century as a result of the henequen agave plant, which was produced nearby and was perfect for creating rope, a material that was required to construct ships and grain-farming machines.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when North American wheat production and shipbuilding were booming and Yucatan twine was in high demand, the henequen fibers were so strong that Yucatan attracted more US investment than any other location. Henequen production increased, earning the plant the name “green gold,” and Yucatan became known as Mexico’s richest state. Henequen was cultivated and processed on more than 70% of Yucatan’s land by 1915, and more than 1,200,000 bales of the plant were exported.

The haciendas expanded dramatically in size and complexity during this time, with expansive grounds that featured farms, henequen-processing facilities, churches, stores, and worker housing. They resemble independent nations in many ways; some even had their own currencies and law.

It should be no surprise that these haciendas were ruled by powerful landowners of Spanish descent who frequently forced the native Maya people into labor against their will.

Adventurous tourists can find their way to the other haciendas that are scattered around this region of the Yucatan peninsula by asking locals for instructions. Their presence is noticeable everywhere, from overgrown ruins in the dark, dense woods to decaying old structures just outside small villages and towns. Some may be accessed by buses or rented taxis, while others require a 4×4 vehicle or a motorcycle. A narrative of rebuilding and remembering is gradually taking the place of one of power, wealth, oppression, and ruin.

Read More:

Rescue Mission for Beluga Whale stuck in Seine River